We all know that the practice of extracting potent tinctures and potions from plants goes back for centuries, but somehow absent from my own understanding of the traditional use of herbs and fauna in medicine was the role of abbeys as some of our earliest apothecaries. During the Middle Ages in particular, monks and medical students used plants to cure all matter of ills and beauty problems. Luckily, some of the most important medicinal gardens in Europe have been preserved for posterity and research, offering a wide geographical lens on the longstanding use of elixirs and tinctures through the centuries. Since most are also open to the public, enthusiasts get the opportunity to learn about the historic health benefits of the plant universe while also traveling to some of the most beautiful gardens in the world.

These gardens of medicinal plants that were the former centers of research and study for students of apothecary, were largely located on the grounds of monasteries, and occasionally nunneries as well. Monks and nuns built up a sophisticated knowledge of medical botany that crisscrossed Europe. In her book Physica, abbess and healer, Hildegard von Bingen, for example, was one of the pioneers in the study of plants, listing over 500 species and their effects on patients. The monastery at Rupertsberg had an extensive herb garden, and remedies were both prepared for her religious order but also for people from the surrounding area. In addition to practical cures– migraines were treated with a mixture of aloe, myrrh, and poppy oil mixed with flour for example—Hildegard’s main hypothesis was that plants will not only make people healthy but even bring a healed patient further towards religious salvation (the garden is now closed to the public, but her books are fascinating for botany enthusiasts).

Minerva’s Garden, Salerno, Italy.

Minerva’s Garden, Salerno, Italy. While medicinal gardens sprung up all over Europe during the Medieval period–in conjunction with religious orders, universities, and individual patrons– Italy had some of the most famous on the continent. The University of Padova’s garden, for example, dates to 1543 and became a UNESCO designated cultural landmark in 1997. The garden was designed as a square (representing water) within a circle (the globe) and later was enclosed by a wall to stop thieves from snatching the increasingly valuable samples with their medical benefits. The plants in this garden were particularly varied as they arrived from all over the world; Venice’s network of trade routes meant foraging for “exotic” herbs and plants became that much easier. In addition to the garden itself, the property includes a museum housing a mindboggling 500,000 dried samples of various plants, some dating all the way back to the end of the 18th century.

Gardens like Padova’s are also essential to preserving certain plants from extinction and maintaining biodiversity. “Botanical Gardens play an important role in the conservation ex situ of threatened species through the cultivation outside their natural habitats, the collection of seeds in the wild, and their storage in germplasm banks,” explains Dr. Mariacristina Villani, one of the Garden’s botanists. “Other important activities are carried out in the field of education and communication, on the one hand stressing the value of plants for healing purposes, and on the other hand the need for the conservation of species and of the environment they live in. Research on medicinal plants in Botanical Gardens include the screening of the medicinal properties of plants not yet in use, the isolation and chemical identification of their active compounds, agronomic techniques (i. e. cultivation under different soil or climatic conditions), ecological requirements (germination physiology, growth rates).”

Victoria boliviana water lily, Minerva’s Garden.

Victoria boliviana water lily, Minerva’s Garden. Don’t miss a guided tour of the gardens for a full overview of the green gem, from the garden’s architecture, the use of the plants in medicine, and new eco initiatives including a solar active building. “The collection of medicinal plants of Padua Botanical Garden includes more than 200 species currently used in medicine (e.g. Azadirachta indica, Leonurus cardiaca, Hypericum perforatum) but also plants that were used in the past and not considered therapeutically valid today (Delphinium staphisagria, Aconitum napellus),” continues Villani. (ortobotanicopd.it).

Italy’s Salerno’s Giardino della Minerva is also considered one of the world’s most important natural pharmacies, a showcase of these type of therapeutic oases known as the “lettura dei Semplici.” A “simple” was an herb or plant used singly on an ailment. Practitioners believed that illness was caused by an imbalance in the four humors (based on the four elements)–blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm. When they were unbalanced, their physician—using herbs and flowers–brought their patients back into equilibrium. And gardens like Giardino della Minerva provided the “simple” remedy. The property has other useful assets that are also easy on the eye with a complex water distribution system, comprised of channels, pools and fountains, plus a pleasant microclimate even in late fall. Its tucked away location on the Amalfi Coast combines moisture and warmth, giving the plant charges the perfect environment for growth. And for a mere three euros, one can visit the spot in the city center with its sweeping views over the sea (giardinodellaminerva.it)

The University of Padova Botanical Garden.

The University of Padova Botanical Garden. Further west, in Scotland, one of the most important Physic gardens can be traced back to a monastic garden now known as Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh. The medicinal garden, or “physic” garden as it was known, can be officially linked back to Charlemagne, who ordained that medicine should be taught at cathedral schools under the name Physic. The original layout, with its 90 medicinal plant species, were overseen by Edinburgh’s top physicians. Spotted lungwort was thought to cure pulmonary infections, hairy kidneywort was believed to stop epileptic fits, scurvy grass was used as a remedy for sailors after long voyages, and birthwort for helping with childbirth.

Garden designer Catherine FitzGerald was one of the pros brought on to revive the medieval gardens that were once cared for by the monks residing in the adjacent abbey, pharmacists who arrived for plants for their remedies, and students to learn about the medicinal properties of the garden’s bounty.

“I was always fascinated by the idea of the Medieval monastic garden – the medicinal plants cultivated by the monks, how they were used and the lore attached to them. There is also something about the order and geometry of how they were laid out that is deeply satisfying and the fact that the monks spent so much time in them gardening as well as contemplating. I was lucky enough to grow up in house which had a walled kitchen garden and we grew many herbs – I knew the wonderful feeling of calm that drinking Lemon verbena tea gave me and the extraordinary flavors of less commonly used herbs such as lovage, sweet Cicely and Hyssop,” says Fitzgerald. “So it was very exciting to be asked to help with the design and planting of the re-imagined 17th century Historic Physic Garden at the Palace of Holyrood. We planted exotic and native medicinal plants which would have been grown in the 17th century and we arranged them by use – there were sections for culinary herbs herbs used for dying, washing and insecticides, herbs used for healing and there was a bed for herbs particularly associated with Scotland. The garden is near the entrance to the Palace and is a welcoming space which encourages people to spend time learning about the herbs which had been grown there in the 17th century as being well as an ordered peaceful haven in which to contemplate the plants just as those early monks did.”

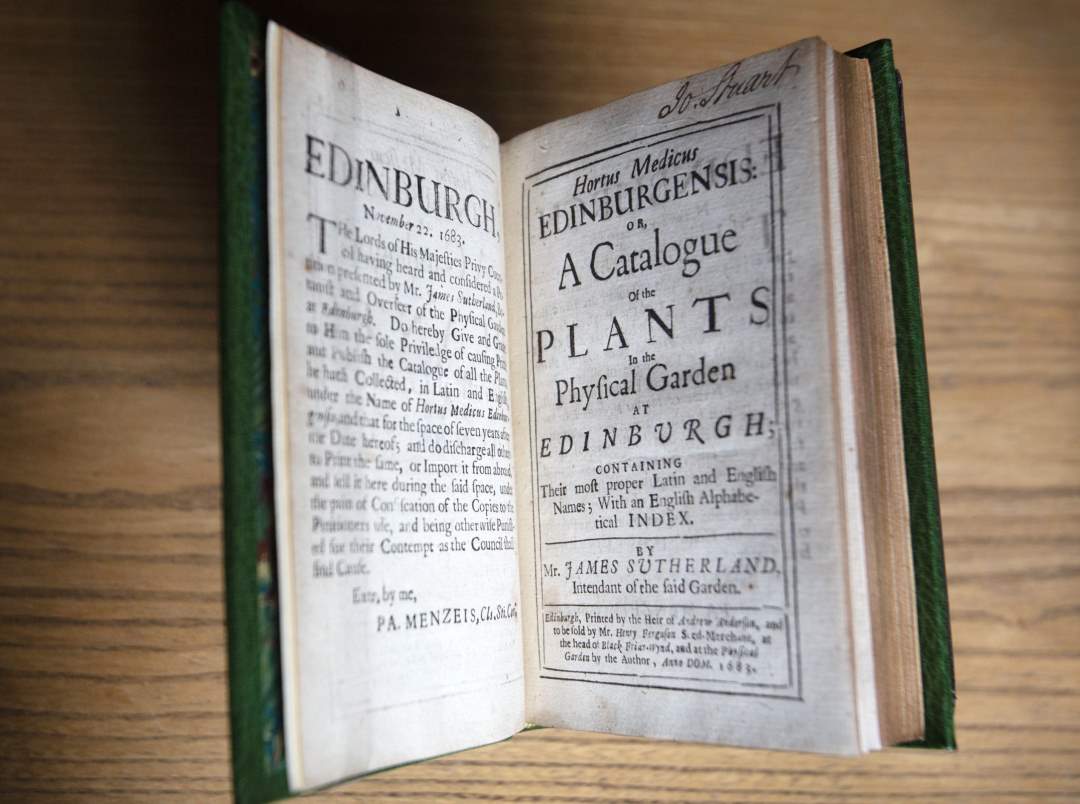

A historical plant guide at Chelsea Physic Garden.

A historical plant guide at Chelsea Physic Garden. Holyrood Palace’s list of plants and their uses is must reading for its humor as much as education with writings from Pliny to Charlemagne and Dioscorides. Bugle, for example, “being beaten small with figs and given like a pill it mollifies ye belly,” Madonna Lily, “cleareth ye faces and makes them without wrinkles,” Acanthus mollis “have power to drive humors to their places,” and Eldeer “softens ye Matrix and opens ye passages.” (rct.uk/visit/pal- ace-of-holyroodhouse).

In London, the Chelsea Physic is also among the world’s most respected natural pharmacies, with about 4000 medicinal plants growing in a microclimate along the River Thames. Established by the creatively named Worshipful Society of Apothecaries in 1673, the garden became a one stop for these enthusiasts to grow and learn about medicinal plants in the 17th and 18th century. Although apothecaries are no longer trained on site, medical students with a passion for plant-based medicine (and other devotees) come to study this discipline’s long history.

Plants at the Chelsea Physic are ingeniously categorized by room. Highlights include the World Medicine collection with plants used all over the globe from shamans to healers, the Dioscorides room with the samples of plants first listed by first-century Greek pharmacologist and physician Dioscorides, and the plants that were grown by the apothecaries in the 17th and 19th century right on site (chelseaphysicgarden.co.uk). (Nearby the Kew Gardens are also amust stop with over 800 acres of plants including an important section used for research and education on medicinal plants).

Other medicinal gardens worth the pilgrimage include the Botanical Garden in Uppsala, Sweden, with more than 8000 mostly wild species; Oslo’s, founded in 1814, and Norway’s oldest scientific gardens, with over 35,000 plants; and the Netherlands’ Leiden, founded in 1590 as a Hortus Medicus garden for medical students.

Some aficionados of medicinal gardens are recreating them at home. Author Maggie O’ Farrell became obsessed with such cures while writing her novel about Shakespeare’s only son, Hamnet. Her research included reading a book of Elizabethan cures. She began to test a few out herself, and now she’s in possession of a floor to ceiling cupboard for her vials including rose elixir, yellow ginger, among others. Outside, therapeutic plants growing include echinacea, dogrose and rosehips. In an article for the Financial Times, she recounts how she became increasingly fascinated by the natural remedies of plants: the nettles that literally soften stings after they were boiled, aloe vera which helps sun burns and eczema, and wild chamomile for digestion, among others. “Growing plants and storing up their produce is an ancient act of hope,” she writes, “a promise to yourself and others that you’ll still be around to reap the benefits.” Thankfully, even long after the monks, nuns, and medical students of medieval times have gone, their hundreds of years of accumulated botanical wisdom have endured.